When I came across the word "Imposter Syndrome" a few years ago, it was an absolute game-changer for me. Did it mean that I wasn't the only one who had been sweating blood all her life, convinced that it was only a matter of time before everyone realized that she wasn't good at anything, as she had led everyone to believe? Besides me, many other people live with the fear of being exposed, that what they present as an accomplishment or ability simply comes from having fooled everyone?

I have always found it mind-blowing and empowering to discover that there is a name for something that is churning inside me. Could this possibly mean that my self-image, of how I am as a person and what I do is largely shaped by being being inadequate, was not because I was actually so deficient and inadequate by being Sohra, but because it is a common, widespread pattern to think this way about oneself?

The next game-changer came when I came across posts on Instagram that linked Imposter Syndrome to systemic systems of oppression like patriarchy and White Supremacy, because I understood - this isn't about random self-doubt.

For some time now, in certain moments of doubt or uncertainty, I have been asking myself a question that has become an important compass for me: who is benefiting? And in this context, the answer to who is benefitting from my self-doubt, from my conviction that I am not enough, not performing well enough, not good enough at what I do is - capitalism. Patriarchy. White Supremacy. These systems deny us that we automatically acquire our unconditional worth as human beings at birth, but gaslight us into thinking we have to earn our worth. And especially people who like to achieve, who are ambitious, after all, can't stand not being good enough, so we plod and plod, in the helpless hope that maybe we'll get to the point where it feels to us like, "I've earned this success!" And that might mean, for example, "I deserve to be happy with myself." or, "I deserve a break." or even, "I'm allowed to make mistakes. I'm allowed to disappoint expectations. I'm allowed to fail to accomplish things. I'm allowed to set limits."

Oppressive systems thrive on applying pressure, it's already in the word. Oppressive systems not only make us feel small, but they continually light a fire under us, telling us that our worth is dependent on our performance, on our productivity. And marginalized people in particular have internalized that. My father told me early on, "As a foreigner in this country, you have to be twice as good as everyone else." Who benefits from that? White Supremacy benefits because brown and black people internalize "Our labor is worth less". And capitalism benefits because we plow and plow and plow to make up for this perceived deficit.

That's not a flaw in the capitalist system, that's by design. This is how capitalism works. Blair Imani describes it brilliantly in one of her one-minute explainer videos. Capitalism is about paying people as little as possible for their work, and you they would even pay people at the lowest points of the supply chain even nothing, if you could get away with it. And we don't even have to look back hundreds of years to slavery to know that. It was about 13 years ago when an acquaintance who had started his own business came back from China after a long business trip, and he excitedly said, "And you don't even have to pay the workers in the beginning!" That sounds extreme, but it's not very uncommon.

For example, companies in this country like to distinguish themselves by having production carried out in so-called workshops for the disabled, and we all fall for the idea that this is a good thing because we have all learned the work of disabled people, people with disabilities, can't be worth much so it's a good deed to put up with that and give them orders anyway. And this then amounts to disabled people working in these workshops for an hourly wage of € 1.35, and enabling companies to achieve conceivably low production costs. I first learned how problematic and discriminatory the system of these workshops is in the highly recommended episode "Do we all have a chance at a career?" (German) of Ninia Lagrande's podcast "All Inclusive," in which she talks about it with inclusion and accessibility activist Raul Krauthausen. And after that, I learned more from activist Lukas Krämer about how unjust and ableist the working conditions are in these workshops.

Ableism = upvaluing and devaluing people based on their abilities, which leads to discrimination against chronically ill and/or disabled people/people with disabilities

We assign different values to people's work, but not because the work is not of essential importance to us, but because we assign different values to the people behind it. This leads to the different pay gaps we know. But also to how we deal with care work in the (supposedly) private sphere.

Emilia Roig, author of "Why We Matter. The End of Oppression" (in my view one of the most important books of our time) and founder of the Center for Intersectional Justice in Berlin, pointed out on her Instagram profile a few days ago that how we deal with household and care work is also shaped by this: there is no recognition that we have to learn these things, that it therefore definitely requires a competence that we have to acquire. As a result, in heterosexual relationships, women are seen as fussy or nagging if they have certain demands about how these tasks should be done when they are (sometimes) taken over by their husbands; while it is not seen as fussy or nagging to have certain demands when it comes to repairs or arranging finances.

Looking at which work we assign which value makes it clear again and again - marginalized people hardly have a chance to develop a healthy, objective or even friendly view of their performance and the value of their work.

For the work sector, I think it is the responsibility especially of those companies that, for example, have social goals or "flat hierarchies". To cultivate a work ethic that takes these privilege and power imbalances into account, and does not place itself at the service of the power and performance system of capitalism, but rather keeps the well-being of all people who work there in mind, from the cleaning staff to the executive floor, not in order to increase productivity, but because we as human beings deserve to feel good in and with our work spaces, and that our work is valued appropriately and fairly, both ideally and monetarily.

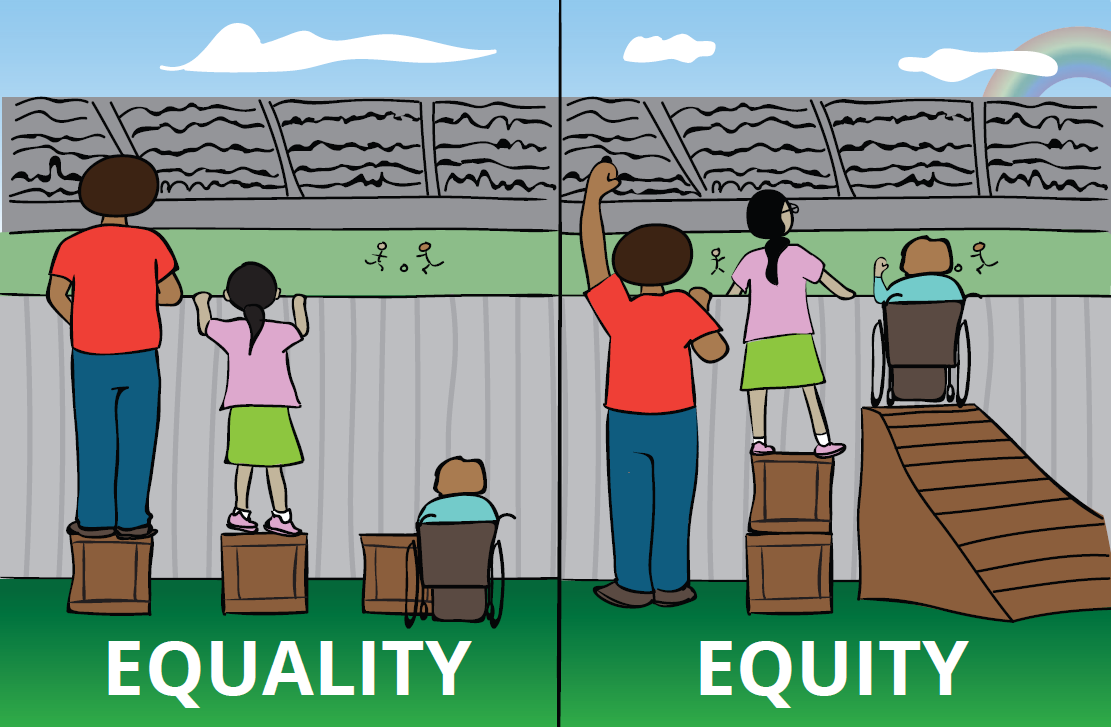

Even equality doesn't bring us to the goal, what we need is equity. An understanding of justice that does not strive for the same for everyone, but looks at who needs what for equal opportunities and to be well provided for? In this sense, would it be fair if a childless man (single or perhaps even in a partnership that provides a second income in the household) received the same salary or the same number of vacation days for the same work as a single mother?

Photo Credit: Equity Tools

Photo Credit: Equity Tools

I love the work of The Nap Ministry. Through them, I've learned that rest and quiet is a matter of social justice:

Photo Credit: The Napindustry/Instagram

The fact that my life is significantly characterized by stress and restlessness started eleven years ago when I became a single parent. This is no coincidence- especially for parents, permanent stress is accepted as a normalized condition, and this situation is exacerbated even more drastically when marginalizing factors such as being a single parent, being (chronically) ill or disabled, or having a sick/disabled child.

I've been wanting to change that for a long time, to slow down, to calm down, and the other day I realized that for years I've been resolving that I need to bang *this one project* out because it's so on my mind, and when I get it done, relaxation will set in. But that won't happen, because there's always another very important project coming up. It's not like *this one project* is actually so mega important that I can't and shouldn't relax until it's done.

What's called Imposter Syndrome, which is really an intentional, hierarchy-driven work culture designed to get people to exploit themselves, has taught us that we're not allowed to just rest and relax. That's why we can't let the checkmarks on our to-do list determine whether and how much we rest; we have to practice it, we have to actively decide, "NOW I'm resting." Most of us have been so tired for so long.

We are not impostors*. Anything you can manage is enough.

Photo Credit: The Nap Ministry/Instagram

I wish for all of us to explore together how resting requires less courage.

----

In this column, presented in collaboration with our friends from Wildling Shoes, we want to give more space and visibility to the issues of anti-discrimination, belonging, and intersectionality in the workplace. Through articles, interviews, and diverse perspectives, we aim to both challenge and inspire those working in the impact sector - while encouraging them to create authentically lived workspaces that foster more belonging and less discrimination. By gaining new perspectives and engaging in a shared dialogue, we can take a collective step toward radical systems change in the impact sector - from "power over" and "power for" to "power with."

Our columnist for 2022 is Sohra Behmanesh. She lives with her family in Berlin, works as a freelance anti-racism trainer, and finds caring and empathy just as superb as intersectionality.

Find more Belonging articles here: https://www.tbd.community/en/t/to-belonging

Photo Credit:

Cover Photo: Михаил Секацкий